Six years into the bull market and investors are getting worried about stock market valuations. Are stocks too expensive?

Since its closing low of 676 in March 2009 the S&P 500 has jumped 208% with hardly a hiccup along the way. That puts the current bull market at just over 76 months, well over the average of 11 bull markets since 1932 which lasted 61 months.

That’s enough to put some stock market prognosticators on edge. Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller has been a regular guest on CNBC this year, recently warning investors that stocks looked expensive and that the price-earnings ratio, adjusted over ten-years, has only been higher in 2000 and 1929. Shiller says that the U.S. is one of the world’s most expensive markets and suggests investors diversify internationally.

But bull markets don’t die of old age and other pundits have provided a different view. Jurrien Timmer, global macro director at Fidelity Investments, has said that stocks are at fair value if you include earnings growth and interest rates.

With so many conflicting views, I thought I would look at the numbers and provide some rationale for individual investors.

How expensive is this six-year bull market?

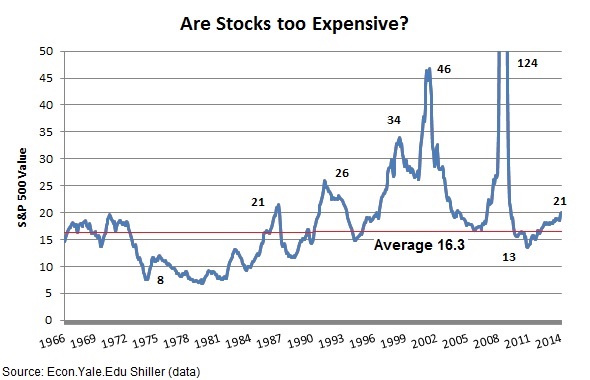

The S&P 500 index is trading for 21.3 times trailing earnings of the companies in the index. You might here it as high as 26.7 times earnings on Shiller’s cyclically-adjusted scale which takes a ten-year average earnings to smooth out changes in the business cycle.

Either way, it’s higher than the historical average of about 16.3 times earnings going back five decades though it’s been higher many times. I’ve graphed out the commonly used trailing P/E below along with the average. By adjusting his data by the CPI and taking an average, Professor Shiller’s estimate puts the current P/E higher than the 2009 peak but still lower than in 2000.

Trailing earnings for the index dropped 92% over the 22 months to March 2009 which pushed price-earnings off the charts. While the current valuation is 28% higher than the average, it’s still well off four notable peaks going back 30 years.

So the argument by the economist at Fidelity must be right, stocks are not expensive…right?

Fidelity is arguing an earnings discount model to value the market on future earnings. The model discounts future earnings by the U.S. Treasury rate plus a risk premium to get current earnings value. Basically saying that since stocks are ownership of future profits, you should value them as such and discount back to today’s dollars. With rates extremely low, the current value of future earnings bound to be higher.

This is always what starts worrying me, when analysts must rely on expectations for future earnings to justify a market valuation. We heard it in the late 90s when analysts talked about the ‘new economy’ and how earnings growth for internet stocks would be in the double- or triple-digits for years, and so justify sky-high valuations.

It hinges on expectations for earnings years into the future, something analysts have proven terrible at estimating.

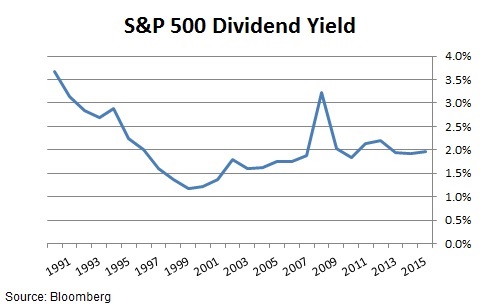

Closer to home, the dividend yield has picked up a little since earlier in the millennium but still hovers around two percent. A huge increase in cash return through increased debt borrowing has barely kept up with soaring stock prices and yields are still nothing to get excited about.

Despite the current market jitters, I’m not really worried about Greece. At about $283 billion, the economy of Greece is about the size of the Miami metropolitan area. Most of the sovereign debt has been shifted to the European Central Bank and other governmental organizations so there isn’t likely to be much fallout in a default.

While the U.S. is talking about higher interest rates, central bankers in Europe and Japan are still pumping the system with hundreds of billions in currency. The U.S. economy is expected to grow by about 3% this year and there are signs of life in the European economy.

China’s slowing economy and its plunging stock market are a bigger issue, especially for commodity prices and countries dependent on exports.

So we are really back where we started with conflicting perspectives. Stocks are expensive relative to the historical average but not absurdly so. The macroeconomic backdrop is good in some places yet warning signs appear in others. What is an investor to do?

Should even long-term investors be worried?

I am not generally a fan of market timing, instead favoring a continuous investment in stocks with great long-term fundamentals. Besides death and taxes, the only sure thing in this world is that the stock market will rise and fall every business cycle. Trying to jump in and out leaves your portfolio open to panic-selling at the bottom and euphoric buying at the top.

That said, I’m also a closet value investor and do not relish the idea of putting all my money into stocks when they are trading at a 28% premium against the historical average.

The solution is grounded in the very basics of investing, diversification. Everyone should hold a mix of stocks and bonds in their portfolio. Bonds provide a fixed return, if held to maturity, and relative price stability against the constant volatility in stocks. Stocks offer the upside of higher returns even if you have to stomach a roller-coaster every once in a while.

Younger investors may only target about 20% or so of their portfolio for bonds while those closer to retirement might hold most of their portfolio, say as high as 80%, in the safety of fixed-income. When bull markets take stock values higher, these percentages can go out of whack as your bond investments lag and the stock portion zooms higher. When markets come down quickly, investors regret not keeping to their planned allocations.

It might be time to reevaluate your allocation, not necessarily selling stocks but investing more in bonds to bring their percentage of the portfolio back up. Instead of committing 70% of your coming deposits to stocks and 30% to bonds, switch to 30% to stocks and 70% to bonds. This will still give allow you to participate in higher stock prices but will protect your downside when the market turns.

Stocks may not be expensive but the best case is probably for fairly valued. Even if the market continues higher, it is not likely to jump as it has and dividend yields have barely kept up with prices. Remembering safety in diversification and shifting the amounts you devote to stocks and bonds will offer the best of both worlds, the benefit of higher stock prices with the eventual safety in bonds.